Peace Through Growth: Ending Colombia’s Civil War

The interview was originally published in NOVasia Issue 31 and is republished on The Policy Wire with express permission. For more exciting pieces on international relations from the brightest minds in Korea be sure to checkout their website.

Though the peace agreement between President Juan Santos and Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia’s (FARC) Commander Timochenko was narrowly defeated in a plebiscite on October 2nd, the world’s longest running civil war appears to be in its twilight. The intensity of the fighting has dropped precipitously since its peak in the early 2000s. Organized military groups in Colombia, FARC being the largest but not the only, are steadily losing ground in remote regions, and major cities have been free from daily terrorism for years.

Current international coverage has only offered in passing the most basic of accounts of FARC, Colombia’s place in the Cold War and the land disputes that have fed a half-century long civil war. Despite the setback to a negotiated peace, a difficult prospect for any civil war, both Santos and Timochenko have promised to continue a bilateral ceasefire and search for a negotiated peace.

How Liberals Learned to Love Fox News

The interview was originally published in NOVasia Issue 31 and is republished on The Policy Wire with express permission. For more exciting pieces on international relations from the brightest minds in Korea be sure to checkout their website.

Fox News was born from a desire to counteract a perceived bias in the US media landscape. Its recently deposed chairman, Roger Ailes, set out to create a cable news network for an “underserved audience that is hungry for fair and balanced news.” Conservatives since the Nixon-era have consistently argued that major news outlets, both on television and in print, hire more liberal-leaning reporters and that their own political views filter into the reporting they do.

Protesting in Vietnam: It Is Time to Push

On April 6th in Ha Tinh, Vietnam, a central province made up mostly of coastline and fishing boats, dead fish began washing ashore. The stink and the carcasses continued to arrive, eventually claiming 200km of beach and affecting four provinces by April 18th. Without any word from the government, and no offers of relief, fishermen and their families could do nothing but busy themselves with shovels, burying their livelihoods in the sand.

Then, something relatively rare happened in Vietnam, Vietnamese citizens from Hanoi down to HCMC took to the streets, blaming a massive US$10.5 billion steel plant just put into operation by Formosa, a Taiwanese plastics corporation.

Protesting is not done in Vietnam unless one is prepared for physical violence or a trip to the police station. Other internationally recognized human rights don’t enjoy much protection either. Vietnam is one of the worst jailors of bloggers and journalists in the world; political dissidents are routinely beaten and jailed; and religious minorities persecuted.

But even more surprising than the presence of chanting in the streets was that Vietnamese marched in relative peace, with only a few reports of isolated police harassment in Hanoi and central provinces.

The protests continued.

At massive May 8th Mother’s Day rallies organized across the country, authorities had at last had their fill. Police returned to their usual repressive tactics, beating protesters, tear gassing many, and carting away as many as 100 protesters to detention centers where they were interrogated into the night. Despite the routine ending, the fish protests proved remarkable.

Then, two weeks later, President Obama arrived for his first visit to the country. While the Trans Pacific Partnership, lifting the arms embargo, and support against China’s recent maritime aggressions were positive items to discuss, talks eventually turned to human rights issues.

Vietnam made promises to make improvements on the right to religious freedom and freedom of association. The US did as much nudging as they could on political prisoners and Internet freedom, as they always do.

But what about the right to demonstrate without fear?

These recent fish protests, which may be the longest sustained in recent history, demonstrate what appears to be an escalating trend of more vigorous and open protest in Vietnam. The increasing incidence of protests — a 90,000-strong footwear factory strike in HCMC last year or small court protests on behalf of bloggers on trial — is an important development.

Not to detract from the immeasurable importance of a free Internet, but it seems perhaps the time may be ripe to push for freedom in the streets in tandem with Internet freedom. The growing daring of citizens to carry out real-life demonstrations is an outgrowth of citizens’ virtual lives.

There seems little doubt that social media has fueled the rise in public displays of anger and discontent. In a country of 91 million, there are more than 30 million active Facebook users despite years of being blocked. Everyone knows the magic DNS server numbers or VPN software to get around the government’s relatively unsophisticated blocks. Internet penetration is also one of the highest in the region with 48.3 percent of internet users according to the World Bank. Considering the fact that half of Vietnam’s population is under the age of 30, those numbers are only going to increase.

In the two years that I lived in Vietnam, working at a national English-language newspaper and doing independent reporting, Facebook served as the primary tool through which I networked, interviewed sources and got my news. In a country where newspapers and television are state-owned, I learned to seek truths elsewhere.

For a Vietnamese citizen, it means so much more. In Vietnam there is very little room for open civil society. Only non-sensitive associations are given permission to form; newspapers, books, TV and film pass through layers of censors; those who dare to write blogs face jail; and mothers holding hands with their kids at protests are punched and bloodied by officers who should be protecting them.

Online, however, citizens found the space to develop their political voice, even if it’s just sharing a link to a human rights lawyer’s blog. Vietnamese memes can be particularly ingenious; a picture of a traffic cop with a few words becomes an insightful, witty, ironic challenge to the state that can also give the author a protective anonymity as it goes viral.

During the fish crisis, information was shared, theories debated, and protests organized via Facebook. Citizens were government watchdogs, posting videos of protesters being beaten, writing personal accounts of interrogations at detention centers, and sharing screen grabs of blocked mobile and Facebook messages if keywords like ‘fish’ were present. Despite these online censors, Facebook was used to circulate an online petition asking Obama to speak about environmental protection during his visit. Within 48 hours, it had over 100,000 signatures.

As the population develops a stronger and more defiant presence online, it is only a matter of time before it grows beyond the confines of URLs. The fish protests tell us maybe the time is fast approaching.

The fight to free the internet must continue, it is the main vehicle by which civil society will continue to grow, but Vietnamese have proven adept at circumventing government repression online. The focus should move to the next battleground — the asphalt, the parks, the court steps, the spaces where people can look each other in the eye and hear the tremor yet growing steadiness of their voices.

Has the government’s stance on protests radically changed? No. There’s been no shortage of classic crackdowns of late, but here and there we’ve seen some forcing of the government’s hand, even if that hand has payed erratically.

What the government’s relatively more subdued response does show is that the populace’s anger and voice weigh heavier in the balance than they did in the past. It seems protesters have won themselves some extra breathing room, just as long as the extra oxygen doesn’t stoke the fire too much.

Though Vietnam’s 2013 Constitution grants the right to freely assemble and demonstrate in Article 25 — it’s still not really legal. A tricky last clause says that the “practice of these rights shall be provided by the law.” Ergo, protesting isn’t legal until the National Assembly passes another law guaranteeing it.

A draft Law on Demonstrations was supposed to be discussed in March but has been delayed until the October legislative session. It very well may be delayed again for as long as it’s convenient. Even if a law is passed, there are so many loopholes through which the government could justify more bloody silence. It will take a multi-pronged approach to change the law and attitudes, and a lot of patience.

But if mothers and children are willing to face the might of a fist, get back up and do it again, we should be alongside pushing for reform and making more room for them. We should follow the Vietnamese people, onto the streets if they are ready to go.

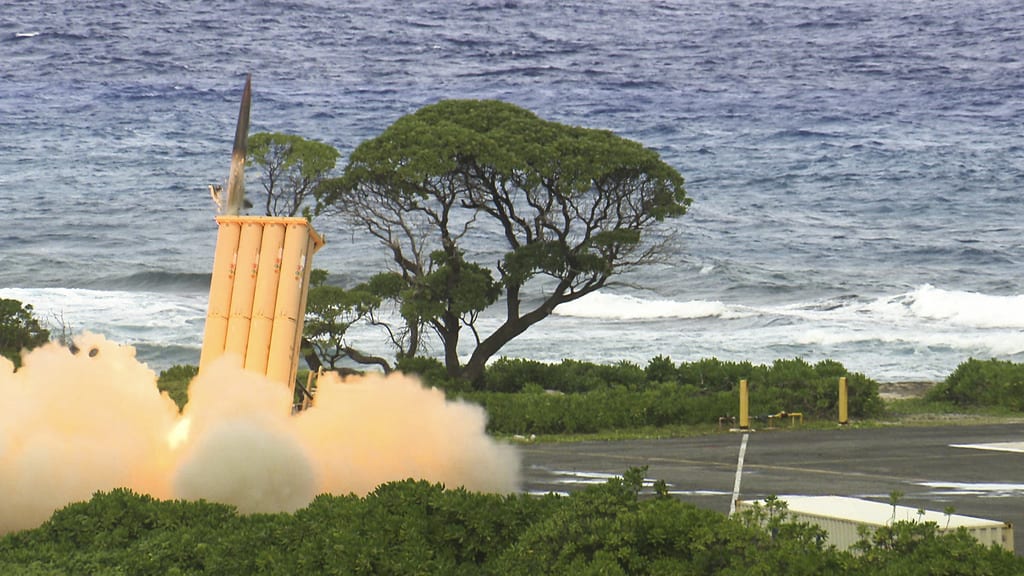

Why THAAD is Good For Nothing

Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) is once again in the news in South Korea, the US, China and around the world. The missile system is capable of connecting with and destroying a ballistic missile in its descent and therefore functions as a last chance defense against nuclear weapons attacks. Given the actions of North Korea that have also been taking up newsprint since the beginning of this year, it is unsurprising that the US would now be more public in its calls for installing the system here in South Korea. The US has been pushing for THAAD to be installed in South Korea for years and intensifies those calls whenever the North conducts a nuclear weapons related test.

To this point however not much progress has ever been made in finalizing a deal to have the US bring in this advanced missile defense system made by Lockheed Martin. It is difficult to believe that despite the official position of both Washington and Seoul that there have been no official discussions between the two nations on placing THAAD. In a recent visit to Seoul, Secretary of State John Kerry told US troops in Yongsan that “we’re talking about THAAD and other things,” but that statement was clarified to mean internal US discussions. At the same time, the ruling conservative Saenuri political party in South Korea has been calling for official discussions.

Large bureaucracies often try to control every step and statement that is made public, but at this point it is impossible to believe that there have not been some discussions between officials over the years. Newspapers are reporting that talks are increasing and there seems to be a level of inevitability in the reporting. Introducing a system to effectively block the nuclear threat posed by the North Korean government would be an obvious choice that seemingly no one could oppose. If the North Korean nuclear threat could be canceled out then that government’s ability to hold Seoul, Tokyo or any other city hostage would disappear. The reality however is not so clear-cut and there are a variety of reasons for the allies to choose other methods of deterrence.

First of all, while the nuclear threat may be sexy, scary, and built for news coverage, in an actual military engagement it would be bizarre to detonate a nuclear bomb only miles from your own territory. On top of this, the North Korean conventional capabilities are already a sincere threat to Seoul and removing the nuclear threat to Seoul does not increase leverage over the Kim regime in any meaningful way. A counter argument would be that North Korea’s nuclear program is also a threat to Japan, the US and others where the regime’s conventional weapons are not a threat. But this has nothing to do with installing THAAD in South Korea. The US official position is that the system only intercepts an incoming missile on its descent, meaning that THAAD cannot and is not designed to intercept a missile as it leaves North Korea on its way to Tokyo or Los Angeles.

Second of all, the chances of North Korea actually using its nuclear capacity would seem to already be well deterred. Any nuclear strike by the already isolated regime would result in its complete destruction. It would be hard to imagine its old ally, the People’s Republic of China, continuing to back the regime after it preemptively started a nuclear holocaust in China’s backyard. Without a significant level of support from China, North Korea stands no chance in a war, nuclear or otherwise, against the US and the South Korean forces.

Proponents of THAAD would argue that the North Korean regime is unstable and unpredictable. It would be hard to argue that point, although being unpredictable and committing national suicide are not the same thing. Proponents of THAAD would say that even if the possibility of a nuclear attack on its neighbor to the south is extremely low, THAAD could and would save millions of lives. This point is also hard to argue. Backed into a corner the Kim regime would likely try to throw all of its capabilities at the wall and hope that something sticks.

The benefits of installing THAAD are simply to save lives in the nearly unimaginable situation that North Korea would use an intermediate ballistic missile attached with a miniaturized nuclear warhead against the near enemy that can already be targeted with conventional weapons. Their capacity to deploy such a weapon is uncertain and certainly the number of them is extremely limited. Over the years US military analysts have stated publicly that the level of development in the North Korean nuclear program is not known to the US. Essentially, the US and the world knows that the regime has produced nuclear weapons, but they are unsure if they are able to make the weapon small enough to fit onto a missile. Washington knows that Pyongyang has intermediate range missile capabilities. However, it is not sure how reliable they are nor if they could reach the continental US. It is very likely that the security community knows more detailed aspects of the regime’s program than it makes public. This does not change the fact that its capabilities are not completely known and its own public statements are unreliable and bombastic.

While the publicly stated benefits would seem to be minuscule, the publicly known costs are large. China and Russia have both spoken out strongly against the deployment of THAAD on the Korean Peninsula. Because of its sophisticated radar tracking system, the two nations fear that THAAD will be used to spy. They also fear that THAAD’s actual capabilities are greater than the US claims and that THAAD could be used to intercept Chinese or Russian missiles in their ascent. China has real fears that the missile defense system is in reality designed to deter its own nuclear arsenal and that North Korea’s provocative tests are providing cover for a US containment of China.

While official US policy is that THAAD cannot and is not designed to counter China weapon systems, if that were the case it would seem that THAAD could be a double win for the US. Sadly, it is not. THAAD would represent an escalation of tensions between the two largest economies in the world, in a region that is already on pins and needles. East Asian military spending is rising and island disputes are becoming militarized with Chinese artillery installments and US freedom of navigation cruises. The publicly known benefits of THAAD are so few and the publicly known costs are potentially so high that the US and South Korea should find other more productive ways to counter the North Korean threat.

Deconstructing the Context of Appointing the Next UN Figurehead

The UN, as Paul Kennedy so lucidly describes in his book “The Parliament of Man,” is an indispensable global institution. Yet at its core it remains a fallible, if not a blatantly limited institution driven very often by the interests and caprices of its most powerful member states. Come January 1, 2017, this seven-decade-old institution will welcome its new figurehead in what will once again be the culmination of the realities of the shrewdest tenderloins of great power politics.

According to Article 97 of Chapter 15 of the UN Charter, “The Secretary-General shall be appointed by the General Assembly (GA) upon the recommendation of the Security Council (SC).” This clause remains deliberately ambiguous about the qualifications of potential candidates. The closest to specifying the qualifications for appointment came in the form of a 1946 General Assembly Resolution 11/1 saying a candidate must be a “man of eminence and high attainment.” The selection process, according to the same resolution, is to be carried out through a process of secret balloting by the Security Council; the chosen candidate is then recommended to the General Assembly for approval, thus setting the tone for what has become a sort of customary law in the practice of global governance in the post-World War II era.

Early indicators point to the fact that this time around, whoever comes up top will have benefited from one of the toughest political peremptory challenges in recent years than any act of compromise as stipulated by UN custom. It is why the campaign to appoint the next figurehead of the UN will be nothing short of a Shakespearean rendition of The Merchant of Venice at its crudest form in the UN’s backroom Sistine Chapel. Forget for a moment the cosmetic changes in the latest exercise in transparency in the selection process, with the public disclosure of candidate profiles and candidates pitching their cases to the GA. Ultimately, tradition has it that the final call lies squarely in the laps of the SC’s most powerful states—Russia and the US. This is evident in the history of the UN and will remain so for the foreseeable future.

And in this season of American political theatrics, I can’t help but borrow what I consider to be the sexiest of American political jargons—“momentum.” History, geostrategic imperatives and dare I say fate, has placed the momentum in Moscow’s direction the process of choosing Mr. Ban Ki-moon’s successor. Whilst momentum counts for much in the American political psyche, we can gather from Moscow’s recent political posturing to predict how it intends to expend its political capital in the backrooms of the SC.

Tradition dictates that it is Eastern Europe’s turn at the helm of the UN, being that the region has been in the eye of geopolitical turbulence. We have on our hands a Russia bitterly aggrieved that its claim to being the regional hegemon is being challenged from Ukraine to the Baltic regions. Add to the mix the raft of sanctions and counter-sanctions between Russia and the West and you have an opportunity for Moscow to display its geostrategic stealth, as it has done so repeatedly in the last couple of years.

The UN has quite a history of Moscow and Washington clashing over the appointment of the Secretary-General. A good example is how the second term bid of Mr. Trygve Lie was vetoed by the Soviet Union in 1950, leaving the SC deadlocked and unable to recommend a candidate to the GA for confirmation. It was an idealist’s misfortune that led Mr. Lie to incur the wrath of Moscow in his first term by sanctioning the intervention of UN forces in the Korean War. Because the cold warriors were in no mood for compromise, it took the GA to rescue what was left of Mr. Lie’s faltering candidacy through a majority vote to extend his tenure. That was the only time the GA actively intervened in the appointment process. Like Mr. Lie before him, Mr. Boutros Boutros-Ghali was viewed as an undesirable.

Similarly wielding the threat of the veto, Washington hounded Mr. Boutros-Ghali out of the UN in 1996 in favor of my compatriot Mr. Kofi Annan. Mr. Boutros-Ghali was a darling of the developing world who truly believed his allegiance was first and foremost to this constituency, and thus saw no need to subscribe to Washington’s diktat of the post-Cold War New World Order. Unencumbered by Soviet pressure, Washington was incensed at Mr. Boutros-Ghali trying to transform the UN into a countervailing force to American strategic interests. To think that not even the fact that Mr. Boutros-Ghali had the backing of 14 members of the SC, major Western European states and the then Organization of African Unity (OAU) could dissuade Washington from strong-arming its way is indicative of the intricacies of the power dynamics in the SC. In the case of Mr. Lie, that Moscow turned its back on a man who had cut his political teeth in the traditions of the European political left—with Moscow as its citadel, wasn’t as surprising as it smacked of retributive action against a perceived act of insubordination. Rather than the ideological camaraderie, Moscow saw in the good old diplomat a willing participant in the adversarial forces in the SC.

After the unsuccessful bids of India’s Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit in 1953, Norway’s Gro Harlem Brundtland in 1991 and Latvia’s Vaira Vike-Freiberga in 2006, that half of this cycle’s declared candidates are women is very telling of the growing recognition of the need for the world body to be catch up with the progressive essence of having women in senior executive roles. In this regard, having a woman at the helm is certainly long overdue. As the candidates for the Secretary-General converged in New York a few weeks ago for the unprecedented process of pitching their cases before the GA, there is every indication (backroom horse-trading aside) that the likeliest candidate matching both the critical gender factor and geographic rotation will be the Bulgarian head of UNESCO, Irina Bokova.

Rumored to be Moscow’s preferred candidate, Irina Bokova has an impeccable resume that is as compelling as it is undeniably wrought with difficulties. As UNESCO chief, she made it her business to defy Washington in admitting Palestine into the UN’s cultural organization. The use of the veto by the P5 has traditionally been an important determinant of who comes up on top in the appointment of the UN chief. Ms. Bokova has lived long enough to know that both Moscow and Washington don’t take kindly to any semblance of being undermined, which is why it is hard to see how she can escape an American veto in the upcoming straw polls given this sentimental deficit. That she still throws her hat into the contest notwithstanding is in many ways indicative of the strength of the wind propelling her flight. Be that as it may, I see in Bokova’s candidacy the signs of a trial of strength between Moscow and Washington.

Moscow has in the last couple of years firmly held on to its lines on all major geopolitical questions. In fact, if anything it has not shied away from open confrontation and swimming against the tides. What better time for Moscow to bask in the glory of its recent geopolitical triumphs than to use the selection process to demand its pound of flesh.

Donald Kirk – Kim Dae-Jung and Sunshine

In 2000, then President Kim Dae-Jung became the first Korean to receive a Nobel Prize, for his life’s work dedicated to democracy and, to quote the Nobel Committee: “peace and reconciliation with North Korea in particular.” The award was granted shortly after the first North-South Korean summit in June of the same year, and in recognition of the merits of the Sunshine Policy in general. Yet fifteen years later, Kim Dae-Jung’s legacy remains controversial: not only is the success of the policy debatable, but some have also criticized the costs he was willing to pay in the name of reconciliation.

Welcome to the Foreign Policy of Nihilism: Kremlin Style

After going head-to-head with the West over Ukraine, and to a lesser degree over Georgia, Russia is still making waves on the international stage. Speaking at the Munich Security Conference, Premier Dmitri Medvedev minced no words in stating the Kremlin’s reading of the current geopolitical order—a cynical Cold War.[1] The Kremlin is all but confounding its critics and staking its strategic claims more vociferously than at any time in the post-Cold War era. Russia’s recent foreign policy posture is predicated on shrewd nihilism, as demonstrated in Georgia, Ukraine, Libya and Syria. This sense of nihilism owes its origins to a tradition that goes back to pre-revolutionary Russia, seeping into the Marxist-Leninist policies of braggadocios interventionism. It is premised on a crude sense of viewing the world as a contested space of interests that are disguised in value-laden narratives.

The Tragedy of Western Triumphalism in Ukraine

A report by the British House of Lords chaired by Lord Tugendhat concluded that Europe sleepwalked into the conflict in Ukraine through a catastrophic misreading of the mood in the run-up to the crisis. As the report rightly indicated, there is good reason to question the institutional thinking within the Western political elite. Despite President Petro Poroshenko’s initial grandstanding, the needless suffering of Ukrainian people of all political stripes further confounds the logic of the West’s triumphalist attitude going into Ukraine.

Neo-Dynastic Ascension in the East: the Paradox of the Pacific and the Rise of Modern Empires in an Ancient World

Bearing witness to today’s Asia summons to mind an almost classic resurgence of sovereignties, seemingly clashing over that ageless title of Greatest Empire of Them All. Although the warmongering skirmishes of old are not the tactic of choice among these modern kingdoms, the dynastic intensity of ancient times has found a new ascendency in the Far East. (more…)

Scott A. Snyder – Korea as a Middle Power

While South Korea has become a major economic power, it is surrounded by far larger players in Asia. It may never be able to play a leading role in shaping both regional and international affairs, but is currently looking for ways to assert itself on the global stage. These aspirations are typical of what scholars define as a Middle Power – an international actor that is neither small nor large.